♢ Zeitkratzer + Mariam Wallentin – The Shape of Jazz to Come (zeitkratzer / Bocian, 2020)

♢ Barre Phillips / Mike Bullock – At Home (2020)

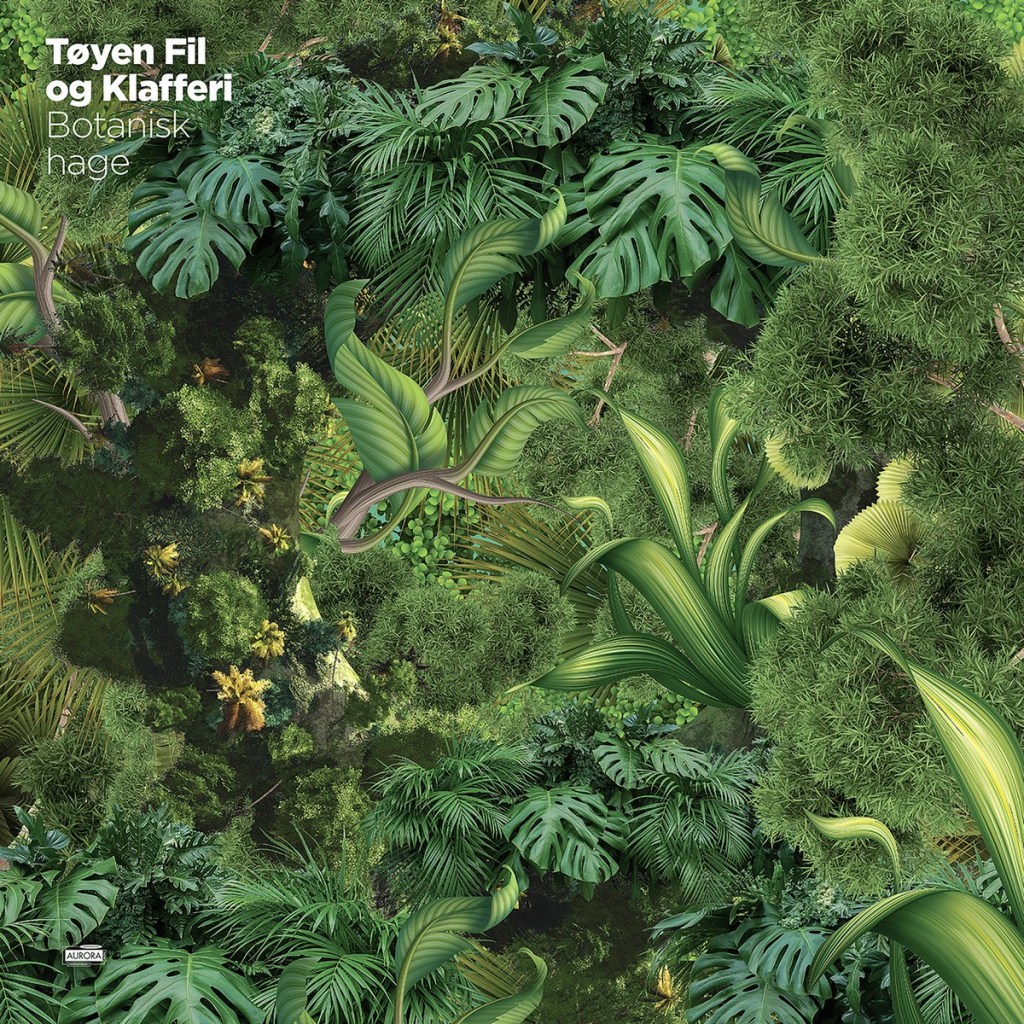

♢ Tøyen Fil og Klafferi – Botanisk hage (Aurora, 2020)

Zeitkratzer + Mariam Wallentin

The Shape of Jazz to Come

zeitkratzer / Bocian, 2020 | avant-jazz/noise

Il jazz a venire avrà una forma spuria ed eternamente mutevole, in qualunque epoca esso troverà nuove iterazioni e contaminazioni spontanee. Lo sapeva lo stesso Ornette Coleman, che con il suo primo indiscusso capolavoro non volle di certo porre un’ipoteca sul futuro della musica afroamericana, quanto aprire le porte e indicare la strada di un percorso evolutivo inesauribile e massimamente inclusivo.

Era solo questione di tempo, prima che i rumoristi impenitenti dell’ensemble zeitkratzer andassero all’attacco della tradizione jazz – del tutto a modo loro, s’intende. Ed è stato decisivo l’incontro con la svedese Mariam Wallentin (metà dei Wildbirds & Peacedrums e vocalist della Fire! Orchestra) per arrivare a concepire una scaletta di standards talvolta anomali, o addirittura improbabili, attraverso i quali sovvertire una volta di più le regole del gioco.

Ma quella presentata nel settembre 2018 al Festival Sacrum Profanum di Cracovia non è una semplice “playlist” di vecchie glorie, bensì una vera e propria suite che, come un ottovolante emozionale, passa con disinvoltura dalla concitazione del blues più fiammeggiante al mesto incedere di lacrimose ballate da piano bar.

Reinhold Friedl, direttore dell’ensemble, rende qui un primo omaggio alla figura di Muhal Richard Abrams, recentemente riportata alla luce da Karlrecords con la compilation di brani elettronici Celestial Birds (nella serie ‘Perihel’ a cura di Friedl stesso). Allo stesso modo la suite degli zeitkratzer ha inizio con “Bird Song”, lato B dell’esordio di Abrams Levels and Degrees of Light (1968), dove i primi sgraziati richiami dei clarinetti introducono l’annuncio profetico in origine affidato al poeta David Moore, e ora reso invece da Wallentin con un recitar-cantando quasi onirico. Subito dopo sono violino e contrabbassi a cigolare furiosamente sulle corde stoppate, oppure con vertiginosi glissati tra gli armonici naturali; entrano poi fiati e percussioni, ulteriori voci diffuse di una selva in crescente fibrillazione, e che superato l’ottavo minuto prorompe nel più rutilante e inarrestabile caos atonale.

Una costruzione tutt’altro che randomica, sia chiaro, poiché conoscendo la perizia e la serietà di Friedl non c’è da dubitare che, in vista della reinterpretazione, egli abbia dissezionato e trascritto tutte le piste del mix prima di affidarle ai suoi talentuosi strumentisti. Oramai pienamente integrata nelle dinamiche di una big band, Mariam si unisce alle grida acute dei fiati in un’estasi ornitologica che scivola lentamente verso il primo episodio del canzoniere classico.

All’atmosfera frivola e danzereccia di “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue” e “Jelly Roll Blues” si alternano senza interruzione i lenti “Cry Me a River” e “Strange Fruit”: da quest’ultima l’ensemble sviscera tutto l’orrore soltanto accennato nell’indimenticabile interpretazione di Billie Holiday, scavando nelle pieghe di un’alterità espressiva che fa dei rumori interstiziali la sua materia prima.

Il più vivace e scombinato stile free-form caratterizza invece la “Drummer Song” di Geri Allen, botta-e-risposta tra Mariam e gli strumentisti che ha il sapore di un divertissement onomatopeico felicemente fine a se stesso. Appena abbozzata dal pianoforte, infine, la dolcissima melodia di “My Funny Valentine”, terreno ideale per l’accorato congedo di Mariam, ospite d’onore di un gran galà sregolato, irriverente e nondimeno fedele alla profonda umanità della cultura jazz.

Line-up: Frank Gratkowski (alto saxophone, bass clarinet); Hayden Chisholm (alto saxophone, clarinet); Hild Sofie Tafjord (french horn); Hilary Jeffery (trombone); Reinhold Friedl (piano, celesta); Maurice de Martin (drums, percussion); Lisa Marie Landgraf (violin); Ulrich Phillipp (double bass); Martin Heinze (double bass); Mariam Wallentin (voice).

Jazz to come will have a spurious and ever-changing shape, in any era where it will be able to find new iterations and spontaneous contaminations. Ornette Coleman himself knew, who with his first undisputed masterpiece certainly didn’t want to put a mortgage on the future of African American music, but instead to open the doors and indicate the path of an inexhaustible and maximally inclusive evolutionary path.

It was only a matter of time before the unrepentant noisers of the zeitkratzer ensemble tackled the jazz tradition – in their own special way, of course. And their meeting with the Swedish Mariam Wallentin (half of Wildbirds & Peacedrums and vocalist of the Fire! Orchestra) was decisive in order to come up with a set of sometimes anomalous, even improbable, standards through which to once more subvert the rules of the game.

But the one presented in September 2018 at the Sacrum Profanum Festival in Krakow isn’t just a “playlist” of oldies, but an actual suite that, like an emotional rollercoaster, passes without effort from the excitement of the most flamboyant blues to the rueful gait of some lachrymose piano bar ballads.

Here the director of the ensemble, Reinhold Friedl, pays a first homage to the figure of Muhal Richard Abrams, recently brought to light by Karlrecords with the compilation of electronic pieces Celestial Birds (as part of the ‘Perihel’ series curated by Friedl himself). Equally, zeitkratzer’s suite begins with “Bird Song”, side B of Abram’s debut Levels and Degrees of Light (1968), where the first gawky calls of the clarinets introduce the prophetic announcement originally entrusted to the poet David Moore, now rendered by Wallentin with an almost dreamlike ‘spoken singing’. Immediately afterwards, the violin and basses creak furiously on the muted strings, or with dizzying glissati through the natural harmonics; woodwinds and percussions then enter, further pervasive voices of a wilderness in growing fibrillation which, after the eighth minute, breaks into the most fiery and relentless atonal chaos.

A construction that is clearly anything but random, since knowing Friedl’s skill and seriousness there’s no doubt that, in view of the reinterpretation, he dissected and transcribed all the tracks of the mix before entrusting them to his talented instrumentalists. By now fully integrated into the dynamics of a big band, Mariam joins the high-pitched cries of the winds in an ornithological ecstasy that slowly glides towards the first episode of the classic songbook.

The frivolous and danceable atmosphere of “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue” and the “Jelly Roll Blues” alternate continuously with the slower pace of “Cry Me a River” and “Strange Fruit”: from the latter the ensemble eviscerates all the horror only hinted at in Billie Holiday’s unforgettable rendition, digging into the folds of an expressive alterity that makes interstitial noises its raw material.

A more lively and scrambled free-form style characterizes Geri Allen’s “Drummer Song”, a back-and-forth between Mariam and the instrumentalists that has the flavor of an onomatopoeic divertissement, a joyful end in itself. Finally, barely outlined by the piano, comes the sweet melody of “My Funny Valentine”, the ideal ground for an heartfelt farewell by Mariam, the guest of honor of an irreverent grand gala, while nonetheless faithful to the profound humanity of jazz culture.

Barre Phillips / Mike Bullock

At Home

self-released, 2020 | free impro

Tante esperienze artistiche e umane possono variamente costellare il percorso di crescita di un musicista: certo è che il contrabbassista statunitense Mike Bullock non potrà mai dimenticare il fatidico ritorno, a distanza di vent’anni, nella dimora francese del leggendario Barre Phillips, col quale ha condiviso giorni di relax e libera improvvisazione.

Tra le montagne a ridosso di Puget-Ville è situata la Chapelle Sainte Philomène, antica chiesa in pietra a fianco della quale Phillips e sua moglie hanno vissuto dai primi anni settanta sino al 2019. Qui il decano dell’avant-jazz ha registrato alcuni album collaborativi della sua lunga carriera, tra cui un duetto con Barry Guy (Arcus, Maya, 1991) e un trio con Joe e Mat Maneri (Angles of Repose, ECM, 2004). L’album digitale a scopo benefico At Home rappresenta, invece, la prima pubblicazione con brani solisti di Phillips eseguiti nello spazio sacro della cappella.

In un anno dove la parola “isolamento” ha coinvolto davvero tutti si sono già affacciate – magari per pura coincidenza – due affascinanti release di musicisti in dialogo con la sola risonanza del loro strumento: ma laddove il il clarinettista Jeremiah Cymerman e il sassofonista Christian Kobi esploravano soprattutto le anomalie timbriche dei fiati, Phillips e Bullock non rinunciano a una seppur tiepida vena melodica, quanto basta a suggerire l’avvento di un momentaneo assorbimento mistico per mezzo del loro imponente arco (entrambi si sono avvalsi del basso Fly Auray di Phillips).

La prima improvvisazione dell’anziano maestro oscilla tra l’invocazione solenne e il lamento, tra gutturali staccato e overtones aeriformi che si fanno strada lungo le secolari pareti; nei successivi take si disegna con sempre maggior dettaglio un autentico atlante dell’anima, assai vicino all’ultimo lascito in studio End to End, punteggiato di vaghi accenni barocchi e inquiete discese nel maelstrom del registro grave. Non meno pregnanti gli interventi di Bullock, la cui personalità si distingue nel tocco tendenzialmente più energico al principio, per poi muovere gradualmente verso le armonie spettrali delle corde appena stoppate, echi di un Novecento ancora vibrante delle sue radicali innovazioni idiomatiche.

L’aurale presenza di Phillips lascia comunque evidenti tracce nel fraseggio del riverente “allievo”, che pur con palpabile entusiasmo mantiene coerente il tono delle riverberanti divagazioni qui raccolte. Si avverte insomma il manifestarsi di un legame simbiotico che annulla il divario generazionale e celebra, piuttosto, la comunione espressiva originata nel singolare contesto spazio-temporale condiviso dai due eccellenti performer.

Many artistic and human experiences can variously punctuate a musician’s growth path: what’s for sure is that the American double bass player Mike Bullock will never forget his fateful return, twenty years later, to the French home of the legendary Barre Phillips, with whom he shared some days of relaxation and free improvisation.

Located among the mountains near Puget-Ville is the Chapelle Sainte Philomène, an ancient stone church near which Phillips and his wife lived from the early seventies until 2019. Here the avant-jazz dean recorded some collaborative albums of his long career, including a duet with Barry Guy (Arcus, Maya, 1991) and a trio with Joe and Mat Maneri (Angles of Repose, ECM, 2004). The benefit digital album At Home represents the first publication with solo pieces performed by Phillips in the sacred space of the chapel.

In a year where the word “isolation” truly involved everyone, two fascinating releases have already appeared – perhaps by pure coincidence – whose authors were in dialogue with just the resonance of their instrument: but where clarinetist Jeremiah Cymerman and saxophonist Christian Kobi especially explored the timbral anomalies of the woodwinds, Phillips and Bullock didn’t renounce a tepid melodic vein, just enough to suggest the advent of a temporary mystical absorption by means of their imposing bowed instrument (both availed themselves of Phillips’ Fly Auray bass).

The first improvisation by the elderly master oscillates between a solemn invocation and a lament, between guttural staccatos and aeriform overtones that make their way along the centuries-old walls; in the subsequent takes, a veritable atlas of the soul is drawn in increasing detail, very much close to his last studio testament End to End, dotted with vague baroque hints and restless descents into the low register’s maelstrom. No less significant are Bullock’s interventions, whose personality stands out with a generally more energetic touch at the beginning, then gradually moving towards the spectral harmonies of the nearly muted strings, echoes of a twentieth century still vibrant with its radical idiomatic innovations.

Phillips’ aural presence, however, leaves evident traces in the phrasing of the reverent “pupil”, who with palpable enthusiasm preserves the tonal consistency of the reverberant digressions gathered here. In short, one can perceive the manifestation of a symbiotic bond that eliminates the generational gap, rather celebrating the expressive communion originated in the singular space-time context shared by the two excellent performers.

Tøyen Fil og Klafferi

Botanisk hage

Aurora, 2020 | contemporary classical

Naturalismo magico, o più semplicemente “ecologia sonora”, sono tra le definizioni possibili per denotare lo stile di un compositore italiano a me molto caro: Salvatore Sciarrino, geniale autodidatta che fu tra i primi a sintonizzarsi attentamente sulle frequenze del regno animale e vegetale, assemblando un diorama immaginario fuori dal tempo e dalla ragione, unicamente devoto all’eccentrica reimmaginazione del Creato.

È impossibile non riconoscere l’illuminata lezione di tale maestro nel linguaggio asemantico dei sei compositori nord-europei qui introdotti, come in uno showcase tematico, dalle fedeli interpretazioni dell’ensemble norvegese Tøyen Fil og Klafferi, che con questo “giardino botanico” (Botanisk hage) firma il proprio debutto discografico.

Sorprende alquanto la rispondenza stilistica fra i più o meno giovani autori (l’età varia dai 38 ai 60 anni), la cui gioiosa eterodossia si esprime non soltanto nelle proprietà fonetiche “estratte” dagli strumenti classici – tecniche estese oramai ben note –, ma talvolta anche nell’utilizzo di oggetti sonori del tutto inconsueti: ad esempio “Achenar” di Ylva Lund Bergner, a fianco del violino e del flauto basso, prevede due performer impegnati con un ciotole di metallo, shaker, tubetti di vitamina C e cartoni di succo con cannuccia.

Spesso, tuttavia, archi e fiati si rivelano sufficienti a generare un’esilarante polifonia rumorista, come negli scricchiolii e ruvidi sfregamenti del “Chinese Telephone” di Klaus Ellerhusen Holm, rivolto specialmente all’enfant terrible tedesco Helmut Lachenmann. L’unica evidente intrusione antropica si verifica nel finale “Radio Days” di Lars Skoglund, dove i caotici estratti di un etere analogico si frappongono alle punteggiature e alle energiche ondate del quartetto, unico residuo organico entro un flusso di schegge verbali e musicali “scorporate”, come una fredda e approssimativa decodifica del reale.

Le musiciste dell’ensemble hanno l’opportunità di mettere in pratica tutta la preparazione tecnica e l’eclettismo di cui sono indubbiamente capaci, affrontando con dinamismo le bizzarre partiture studiate a stretto contatto con i rispettivi autori. Spinta innovativa e passione, carattere ludico e rigore esecutivo sono gli elementi di un’equazione perfetta ed esemplare nell’ambito della nuova musica da camera.

Una selva “addomesticata” di amenità acustiche vi attende tra i solchi di questo imperdibile Lp, corredato da ampie note di copertina le quali, anziché svelarne i segreti, offrono ulteriori suggestioni poetiche a un’esperienza d’ascolto che invoca la fantasia incorrotta di un bambino alla scoperta del mondo naturale.

Tracklist: 1) Hafdís Bjarnadóttir – “Sumar”; 2) Carola Bauckholt – “Luftwurzeln”; 3) Kristine Tjøgersen – “Radiolarie”; 4) Klaus Ellerhusen Holm – “Chinese Telephone”; 5) Ylva Lund Bergner – “Achenar”; 6) Lars Skoglund – “Radio Days”

Line-up: Hanne Rekdal (flutes and bassoon); Kristine Tjøgersen (clarinets); Eira Bjørnstad Foss (violin); Tove Margrethe Erikstad (cello)

Magic naturalism, or more simply “sound ecology”, are among the possible definitions to denote the style of an Italian composer very dear to me: Salvatore Sciarrino, an ingenious self-taught master who was among the first to attentively tune in to the frequencies of the animal and vegetable kingdom, assembling an imaginary diorama out of time and reason, solely devoted to the eccentric reimagination of Creation.

It’s impossible not to recognize his enlightened lesson in the asemantic language of the six Northern European composers introduced here, as in a thematic showcase, through the faithful renditions of the Norwegian ensemble Tøyen Fil og Klafferi (‘Clotheshorse and Pantry’, sic!), who with this “botanical garden” (Botanisk hage) marks its own recording debut.

It’s rather surprising, in fact, the stylistic correspondence among these more or less young authors (aged between 38 and 60), whose joyful unorthodoxy is expressed not just in the phonetic properties “extracted” from classical instruments – extended techniques which are now quite common –, but sometimes also in a selection of totally unusual sound objects: for example “Achenar” by Ylva Lund Bergner, alongside the violin and the bass flute, sees two performers engaging with metal bowls, a shaker, vitamin C tubes and a juice carton with a straw.

Often, however, strings and woodwinds prove sufficient to generate an exhilarating noise polyphony, as in the creaking and coarse rubbing of Klaus Ellerhusen Holm’s “Chinese Telephone”, especially indebted with the German enfant terrible Helmut Lachenmann. The only evident anthropic intrusion occurs in the final piece, Lars Skoglund’s “Radio Days”, where the chaotic excerpts from an analog ether get in the way of the quartet’s punctuations and vigorous surges, the only organic residue within a stream of “disembodied” verbal and musical splinters, like a cold-hearted and sloppy decoding of reality.

The female musicians of the ensemble have the opportunity to put into practice all the technical preparation and eclecticism of which they are undoubtedly capable, dynamically confronting the bizarre scores studied in close contact with their respective authors. Innovative drive and passion, playful character and executive rigor are the elements of a perfect and exemplary equation in the context of new chamber music.

A “domesticated” wilderness of acoustic amenities awaits you between the grooves of this unmissable LP, complete with ample liner notes which, instead of revealing its secrets, offer further poetic suggestions to a listening experience that invokes the uncorrupted fantasy of a child off to discover the natural world.